Our ear: Like a piano with thousands of keys

We usually go to them when it's already too late, when our ears hurt, when they're stuffed with cotton wool or when the whistling sound just won't stop: to the ENT doctors at the University Hospital Zurich.

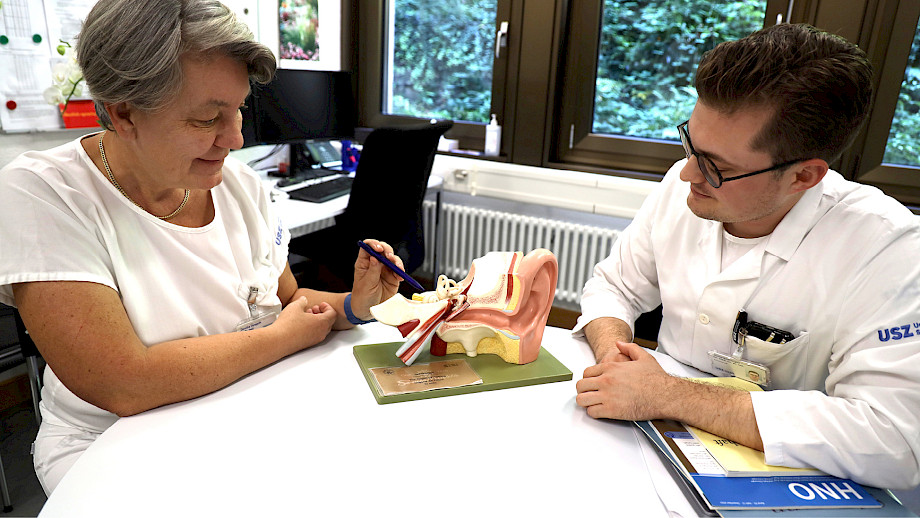

I am greeted by a large model of our hearing organ on the table and behind it the friendly face of Dr David Bächinger. He works as a doctor at the Department of Ear, Nose, Throat and Facial Surgery at the University Hospital Zurich and has been fascinated by the human ear and what it is capable of since his studies in medicine and biology. Together we will embark on a short journey into the human ear canal.

Off to the hammer, anvil and stirrup

David Bächinger is the expert guide on the journey from the pinna, the visible part of the so-called outer ear, towards the inside of the head. As part of the middle ear, which we are all familiar with from the inflammation of the same name, the eardrum is an important landmark, as it seals the auditory canal airtight. The smallest human bones are attached to the eardrum: The malleus, incus and stapes. They pick up vibrations from the air and transfer them to fluids in the so-called inner ear. This consists of the cochlea on the one hand and the organ of balance on the other. An important transmission takes place in the cochlea, which actually looks like a small snail shell: Tiny hair cells convert the mechanical vibrations into electrical impulses. They encode the sound information, which is then transmitted to the brain via the auditory nerve.

A marvel in the snail shell

Thanks to research, new findings are constantly being made about this fragile structure in the human head, says Bächinger: "What we haven't known for so long: The most vulnerable point in the ear is the connection between the nerve fibre and the hair cell, i.e. the plug of this cable into the hair cell, so to speak. And we now know that these structures are already damaged at significantly lower sound levels than the hair cells. This means that the hair cells then lose some of their attached nerve fibres, which leads to more complex functions such as speech comprehension being impaired. And it is also assumed that tinnitus can be caused by this."

Between busy patient appointments, Dr Dorothe Veraguth takes time for us; she is a senior physician in the Clinic for Ear, Nose, Throat and Facial Surgery. With regard to research, she is confident, but qualifies: "Unfortunately, we cannot yet replace these connections to the hair cells or the hair cells themselves. That would be the big goal. But it will certainly take a while, despite intensive research, ten years would be too short. Because the inner ear is very complex." She explains just how complex by comparing it to an instrument: "Each hair cell has the task of recording exactly one frequency of tones or sounds and transmitting them to the auditory nerve. In the inner ear, we have a kind of piano with thousands of keys that transmit the information very finely. And recreating a keyboard with thousands of different cells exactly as it was before, each individual cell for its own frequency, is very demanding."

So the advice from the two experts comes as no surprise: protection is better than repair. "If we want to enjoy music, we need to hear well so that we can really perceive all sounds and all frequencies well. And that means we need to protect our ears as well as possible from excessive noise, from the wear and tear of the tiny hair cells in the inner ear," says Dorothe Veraguth.

Composers with hearing loss

Important figures in the history of music have had to struggle with impaired ears. Dorothe Veraguth and David Bächinger also took a closer look at them in a joint seminar with Laurenz Lütteken from the Institute of Musicology at the University of Zurich: Their patients this time were Beethoven, Smetana and Schumann. In the case of Schumann in particular, the examination of his biography and works is overshadowed by his nervous disorders. Using descriptions from letters, accounts by contemporaries and the household diary with Clara Schumann, Bächinger has worked out the fact and its significance for musicology that Robert Schumann suffered from dizzy spells at a very early age and later also from tinnitus.

"Until now, these complaints have often been dismissed as a mental illness. However, we now have to assume that many of them may be organic, caused by a disease of the inner ear. Because we know from Schumann that he probably had syphilis. And syphilis is notorious for migrating to the inner ear, especially in the later stages, where it can trigger a disease that causes dizziness, tinnitus and hearing loss." For Schumann and other composers, the symptoms certainly had an influence on their works. This was also the case for Smetana, who was around 50 years old when he developed whistling tinnitus as a harbinger of increasing hearing loss. Syphilis was probably the cause in his case too. Due to his deafness, he withdrew from public life, but continued to compose. In his first string quartet "Aus meinem Leben" (From my life), he came to terms with this turning point: In the fourth movement, a long, piercingly high note is suddenly heard - his tinnitus. "A kind of autobiographical note in this late first string quartet," says Bächinger.

The most famous example is probably Beethoven, who already had the first symptoms of hearing loss at around the age of 30: " ... only my ears, which continue to buzz and roar day and night", Beethoven told a friend in 1801. He was dependent on ear trumpets and became increasingly deaf. This had a decisive influence on his life and not least on his perception as a misanthrope. On the other hand, this is the only reason why the conversation notebooks exist as a valuable source, which give us a very intimate insight into his everyday life. "If you take a closer look, however, you also find many testimonies that cast doubt on whether he really heard as badly as often described," explains David Bächinger. "For example, there is a late incident from 1825, two years before his death, in which a friend of Beethoven's let out a scream that he is said to have heard well and laughed about. But there is no doubt that Beethoven had hearing loss."

Dementia prevention and resilience

Beethoven also gave advice on hearing health: "He advised a travelling salesman that baths and country air could improve many things. He also advised against using hearing aids too early, 'machines' as he called them, because he thought that he had preserved his left ear quite well by doing without them." However, David Bächinger and Dorothe Veraguth would no longer agree with the last part of this recommendation. On the contrary: a recent study from the UK, published in April 2023, shows that poor hearing increases the risk of dementia in old age by 42%. Wearing a hearing aid, on the other hand, normalised the risk. "There will be further research into the exact correlations. But it is an important signal that wearing a hearing aid is the only way to eliminate a significant risk factor. Hearing aid acousticians are important partners for us when it comes to further care after acute treatment. A lot has happened in this area in recent years," emphasises Dorothe Veraguth.

How does music sound with a hearing aid?

We asked Zurich-based hearing care professional Michael Stückelberger. He knows the answer from his own experience: hearing loss led him to his current profession around 20 years ago.

How do hearing aids change the perception of orchestral sound?

Hearing aids are extremely focussed on understanding speech. They use a variety of algorithms to optimise acoustic signals. Unfortunately, some of these can lead to overtones being altered in music or a tremolo being heard even though none is being played. This is of course annoying. Hearing aids also work with dynamic compression. Quiet sounds are amplified disproportionately, loud sounds are amplified less or not at all, because otherwise they would be unbearably loud. This reduces the dynamic spectrum of the music, making it sound flatter - similar to sound recordings, which also work with dynamic compression.

Can you enjoy a concert without a hearing aid if your hearing is failing?

Absolutely! Hearing aids are not primarily bought for music. You need them so that you don't lose the context in dialogue, in company or in the theatre. At a symphony concert, it's a shame if you can no longer hear a pianissimo passage with a mild hearing loss. But the music as a whole still "works" because it is perceived very differently to speech. The spoken word must be heard correctly by the ear and then interpreted in the brain and processed into meaningful information. Music does not need this; music goes straight to our emotional centre. That's why it touches us so intensely.

Other studies in the field of listening and especially listening to music have also provided remarkable findings in recent years. For example, an international study by the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics in Frankfurt am Main found that music strengthens resilience in times of crisis - here using the example of the coronavirus lockdown. The director of the research institute, Melanie Wald-Fuhrmann, emphasises that "listening to music and making music offer different ways of coping". These processing options cover three major areas: Listening to music "to regulate depression, anxiety and stress", listening to music and actively making music "as a substitute for social interaction " and "for a sense of belonging and community ", and making music "as a means of self-reflection".

Professional ears

Dorothe Veraguth and David Bächinger also enjoy experiencing this effect of music in the concert hall. Both have a special connection to classical music - she played the bassoon herself during her studies and he still enjoys playing the piano today. "I think when you sit in a live concert, you're really fully involved: with your ears, with your eyes, and you can also feel the moods in the orchestra and in the audience. In other words, all your senses are involved," says Veraguth. "These are the moments when we simply relax or listen intently and don't think about the complex processes in our inner ear," adds Bächinger with a smile. "Only sometimes I wince at some fortissimo passages."

The protection of "professional ears" is also a major concern for Dorothe Veraguth and David Bächinger. On the one hand, they want to establish the term "Professional Ear User" ("PEU") in their specialist area, to a certain extent as a counterpart to the "Professional Voice User", for whom there are already concepts in terms of prevention, diagnostics and therapy. On the other hand, they are working on anchoring their concept of holistic ear health in practice. For around two years now, there has been a specialised ear health centre for "PEU" and - in cooperation with the Zurich University of the Arts - regular seminars in which young musicians, music teachers, composers and sound engineers are taught basic knowledge about the ear. However, Bächinger's circle of "PEU" also includes professional groups with no connection to music, such as speech therapists, ornithologists or sonar technicians - in short, all those people who have an "acquired, above-average auditory perception ability". For them, healthy ears are not only important, but a professional requirement - preferably with all the thousands of "buttons" in the inner ear.

Translated with DeepL.com