He was a universal musician - and a professor in Zurich

Despite its witty title, Paul Hindemith's viola concerto "Der Schwanendreher" is not a funny work. Behind it lies a special chapter in his biography - and a piece of Swiss music history.

"Hindemith, give it to me, get rid of it!" This was a slogan used against the composer. It is still quoted today by sceptics of his music - usually with a cheeky grin on their faces. Yet Paul Hindemith is one of those important figures in German history who can be described without hesitation as a universal musician. He was not only a visionary composer, but also a pedagogue, theorist, concert organiser, writer, conductor and a gifted instrumentalist: Hindemith is regarded as one of the most popular violists in the first half of the 20th century. He is also said to have played all the instruments for which he wrote works himself. Due to his versatile talent, he was called the "Leonardo da Vinci of music" in the contemporary press.

However, his talent could not protect him from the developments after the National Socialists came to power in 1933, which quickly had a negative impact on his work. The situation escalated after a performance of his symphony "Mathis der Maler" conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler in the internationally sensational "Hindemith case", an article in which the conductor spoke out in favour of the ostracised composer's music. On 6 December 1934, Joseph Goebbels then described Hindemith as an "atonal noise maker" in a speech to the Reich Chamber of Culture. Two years later, the sentence quoted above became reality and the performance of his works was banned in Germany. In 1938, he and his wife Gertrud emigrated to Bluche in Valais, and in 1940 he emigrated to the USA.

Until then, Hindemith was in a state of inner emigration. He also travelled to Turkey several times, thus fulfilling an offer from the Turkish government, arranged by Furtwängler, to help build up a musical life according to Central European standards. It was precisely at this time that he composed his "Swan Turner" for viola and small orchestra, which he performed abroad - exclusively, as he never played the solo part in Germany. He only conducted the piece once there, in 1962, when he had long since hung up the viola. Against the background just described, the question arises:

What is a "Schwanendreher"?

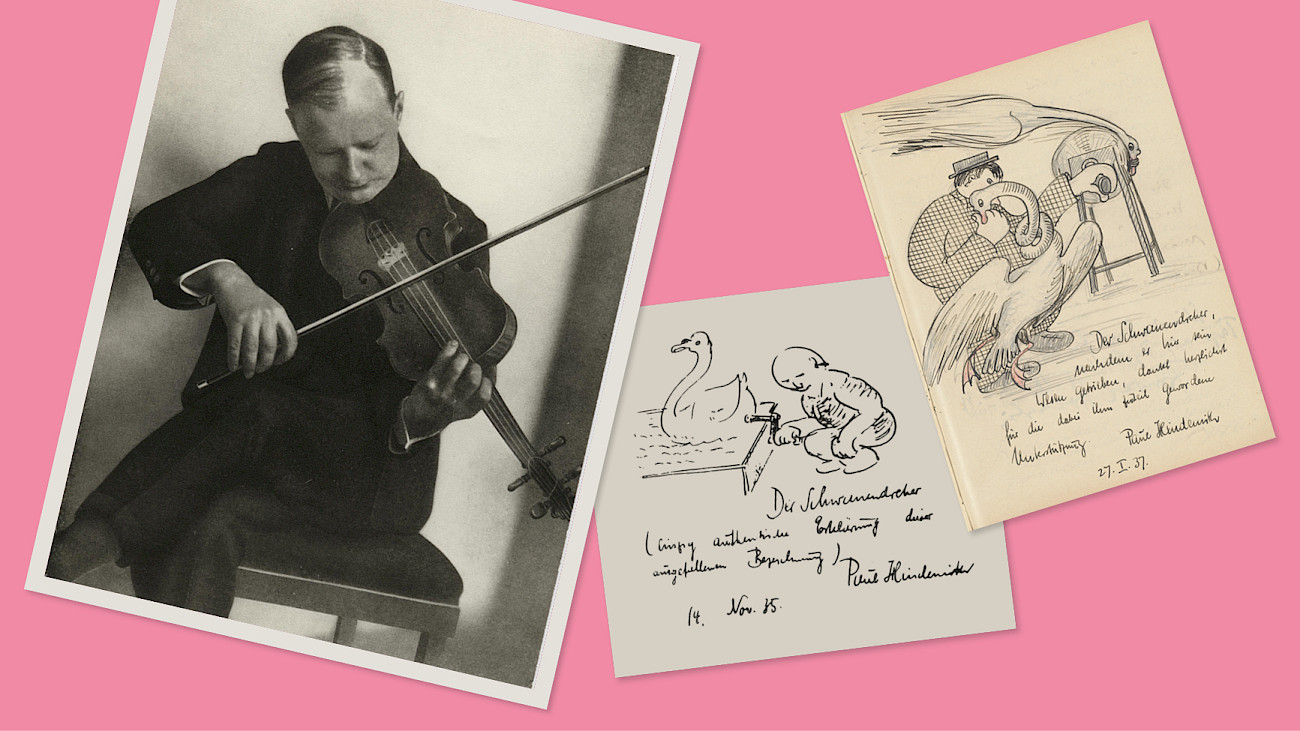

Hindemith had a great deal of humour and self-irony, which was expressed not only in his compositions but also in his numerous drawings. Throughout his life, he drew at every possible opportunity. For example, he left us caricatures of the "swan turner". On 14 November 1935, he sketched the "only authentic explanation of this unusual name", as it says in his caption. It shows a kind of organ grinder spinning the noble bird instead of the instrument.

At first glance, the drawing looks amusing. Hindemith had obviously not lost his sense of humour, although the work was directly related to his painful situation in Germany. In the preface to the score of his composition, he explained: "A minstrel comes into cheerful company and spreads out what he has brought with him from afar: serious and cheerful songs, and finally a dance piece. According to his imagination and ability, he expands and embellishes the tunes as a true musician, preludes and fantasises."

On closer inspection, the autobiographical component of the work becomes even clearer. As the full title of the work reveals, Hindemith's "Schwanendreher" is a "concerto after old folk songs" (taken from the Old German songbook "Volkslieder der Deutschen nach Wort und Weise aus dem 12. bis 17. Jahrhundert" by Franz Magnus Böhme). The eponymous originals of the first and second movements - "Zwischen Berg und tiefem Tal" and "Nun laube, Lindlein, laube!" - tell of parting, pain and separation. "Der Gutzgauch [i.e. the cuckoo who] sat on the fence", which is quoted in the second half of the middle movement, can be understood as the stigmatised, outcast and mocked. The final movement bears the question "Are you not the swan turner?". As Hindemith wrote the work in order to be able to perform it himself, the correct answer would be: "Yes." After all, he was the homeless minstrel who was forced by Nazi policy to perform his music abroad.

However, there are other interpretations of the term. One would be that a "turner" is a "turner" of long-necked objects. Hindemith was probably also familiar with this interpretation. After a performance at the Musikkollegium Winterthur on 27 January 1937, he drew another humorous caricature of the "swan turner" in the so-called "Rychenberger Gastbuch" of his friend and patron Werner Reinhart. It shows a man working on swans in a kind of lathe. Hindemith signed the drawing full of self-irony with the words: "The swan turner, having done his mischief here, thanks you warmly for the support you have given him. Paul Hindemith. 27.1.37."

Zurich and Blonay

Paul Hindemith never played his "Schwanendreher" with the Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich. However, he was a guest violist once: on 28 and 29 January 1929, he performed his Chamber Music No. 5 op. 36/4 under the direction of Willem de Boer. 21 years later - after his emigration to the USA and his return to Europe - he was back in front of the orchestra, now as a conductor.

He was invited back again in 1956 and 1959. At this time, Hindemith was connected to the city of Zurich in a special way: Even though he did not have an academic degree, or even a high school diploma, he was a professor at the Department of Musicology from 1951 to 1958 - making him the first ever full professor for the subject in the history of the University of Zurich. He also taught at Yale University until 1953. He categorically turned down job offers from Germany.

But life on two continents, the many concert tours and commitments were exhausting. The Hindemiths were therefore looking for a retreat where they could be undisturbed and recover from the stresses and strains of everyday life. They found it: In the summer of 1953, the couple moved into the idyllically situated villa "La Chance" in Blonay on Lake Geneva, where they lived for over ten years until Hindemith's death. In her will, the widow Gertrud stipulated that the inheritance should be "converted into a Hindemith Foundation". Which is exactly what happened.

Since then, the Fondation Hindemith has been committed to preserving and disseminating the works of the often misunderstood composer. Violist Tabea Zimmermann is at the forefront of this endeavour as President of the Foundation Board. She has long been dedicated to Hindemith: in 2006 she won the Hindemith Prize of the City of Hanau, in 2013 she became a member of the Board of Trustees of the Fondation Hindemith and in the same year recorded his complete works for viola. She repeatedly focuses on him in her projects and brings his compositions, which for many are more of a love at second sight, closer. For example, in the masterclasses held at the Centre de Musique in Blonay.

Tabea Zimmermann is therefore undoubtedly the ideal soloist for Hindemith's "Schwanendreher", which is one of her favourite concertos. Her interpretations manage to convert even the biggest Hindemith critics, so that after her performances with the Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich in February 2026, it may just be a case of "Hindemith, bring it on!"

Paul Hindemith Archive

Since October 2021, a large part of the estate from Hindemith's villa "La Chance" has been housed at the University of Zurich's Institute of Musicology at Florhofgasse 11. These include the 4700 books from his private library, including around 1330 editions of sheet music and pocket scores, as well as pictures, photographs, furniture, his Grotrian-Steinweg grand piano, handicrafts and a toolbox. The archive's holdings can be used to a limited extent by prior appointment at: hindemith@mwi.uzh.ch.